In our 35 years in B.C., we've met the occasional odd native who is indifferent to the wonder of mountains (or eagles, or seals). Odd, indeed. For us, it was love at first sight when we drove west by van, and the great wall of the Rockies suddenly came into view from a hundred or more miles away.

In our first five years here, we hiked every weekend and became closely acquainted with many mountains. Inevitably, mountains were early subjects when I began to paint -- in the beginning, "imaginary" mountains evoked from the Upside-Down File, such as "Ravenstorm" (circa 1990).

Eventually, we bought a kayak and spent every weekend on the water, coming to know among other things, the drama of mountains meeting shorelines, as in "Above Furry Creek" (1991).

It happens that my mountain paintings were all done on pressed wood panels with applied texture and collage elements. JT cradled them for me, applying wood braces to the back side to prevent warping. "Above Furry Creek" was the largest panel I worked on at 5' x 5' -- and a fast-moving furry creature has been enlisted here to show its scale.

Working on this painting, I became fascinated with how the diagonals and triangles of actual mountain-scapes resemble endless variations on the Eye of God motif.

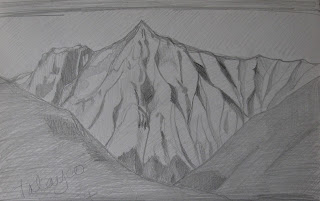

Eventually, we found our cabin property and became immersed in the natural life of the Upper Squamish Valley, living almost half-time year-round for 20 years beneath the mountains of the Tantalus Range. "Mt. Pelion" (shown here) looked down on us from the north.

In my ongoing 2012 studio overhaul, I found among my sketchbooks many records of my Mountain Period, among them my first pencil study for "Above Furry Creek."

...then a small (5" x 5") colour study, collaged from colour chips clipped from magazines.

...then -- most worth finding again -- a quotation from Lama Anagarika Govinda's The Way of the White Clouds that seems to resonate with the Eye of God theme -- and with our own intense response to mountains.

To see the greatness of a mountain, one must keep one's distance; to

understand its form, one must move around it; to experience its moods,

one must see it at sunrise and sunset, at noon and at midnight, in sun

and in rain, in snow and in storm, in summer and in winter and in all

the other seasons. He who can see the mountain like this comes near

to the life of the mountain, a life that is as intense and varied as

that of a human being. Mountains grow and decay, they breathe and

pulsate with life. They attract and collect invisible energies from

their surroundings: the forces of air, of the water, of electricity

and magnetism; they create winds, clouds, thunderstorms, rains,

waterfalls and rivers. They fill their surroundings with active life

and give shelter and food to innumerable beings. Such is the

greatness of mighty mountains.