Of all the early artists who painted in the Adirondacks, most came to the area in their adulthood, loved the wilderness places and landscape enticements, and stayed on for a while and/or came back seasonally.

I've come across only one so far who was born and raised there – maybe not quite "there" but in the foothills area of my little paper mill town; just 20 miles away, in fact, and 100 years before my time. He was Levi Wells Prentice, a farm boy with little formal training whose works garnered notice only decades after his death. I was so intrigued by this Nearby Unknown that I found a book about him on-line and, Dear Reader, I bought it.

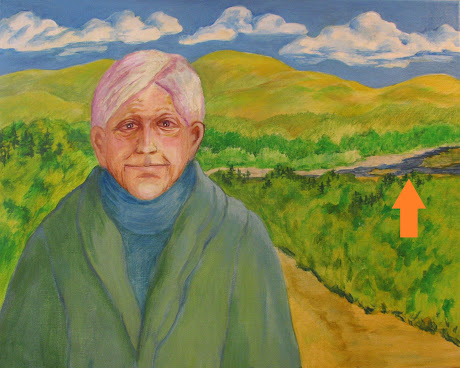

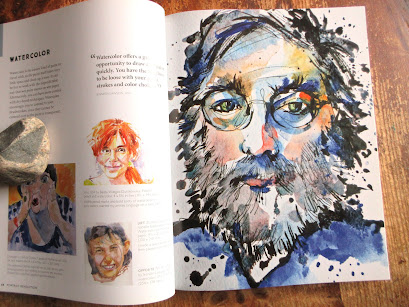

As suggested in this cover painting and the selections here, Prentice had a distinctive style in both his still life paintings and his landscapes. In many cases, they are hyper-realistic in a sense, with strong dark/light contrasts and fiddly attention to little shapes that he has painted more distinctly than the eye would see them in nature.

"Nature Staged" had little to offer about the man himself, and there's not much about him on-line, not even a photo. I could find only a portrait of him painted by an unidentified artist.

Well, that was enough to play around with – and play I did, starting with some quick prototypes and then trying some printing, stamping, collage techniques.

None of this was the least satisfactory so I decided…what the heck. I would try something I'd recently seen in its end stage at a gallery my friend L had whisked me to. I placed two versions of Experimental Prentice on a plastic sheet in the back yard…

…and set a big chunk of ice on top. I expected that when I came back later that day, I'd find some magnificent swirling features – beyond Jackson Pollock's wildest dreams.

No such luck! No magic transitions. Not even a "Framed" version to show for this. Time to move on to Prentice's landscape and my own.

From among his on-line landscapes, I was hopelessly smitten with his "Moose River, Adirondacks" -- for reasons that might be apparent to historians of this blog.

You've seen the Moose River before, where it joins the Black River at the long-ago hometown that marked me for life.

I paired Prentice's painting – which must have been done considerably upstream – with my recent photo of Palisade Creek, at the northern edge of the Capilano Watershed.

I planned to mimic Prentice's style – with the characteristic outlining and details. Determined to "hold the lights" – not get too dark, too soon (my mistake last time), I made a very tentative start.

I thought I was on top of things, but before long (actually, very long; several hours worth of long), I heard myself saying, "What was I thinking??!?!?"

Was I really going to try delineating every branch and leaf in all that expanse of greenery? Nope. Not gonna do it. Instead, I cropped away about 90 square inches, removing strips on either side of the creek.

Pressing on regardless, I finally dubbed this The Finale:-- "Palisade Creek, Capilano Watershed" (copyright 2023)

With all the Adirondack landscapes in my view this summer, I can't help but think of a young boy I once knew – fervent and accomplished angler of freshwater creeks and lakes from the age of 10. I remember him in his mid-50s, delighted when I happened to say, "No fish has ever tasted as good as the rainbow trout you used to catch in the North Country." He might well have fished these very spots along the Moose River.