into the studio between working sessions to see what's happened since

the last time I was there. I'll finish a morning session and then

some hours later be unable to resist opening the door, looking to see

how the morning's painting is going...as if it would be any different

from when I left it.

I've recently realized that this is no laughing matter. In fact,

what's there when I open the door is a sure indicator of whether

things are going well or not. When things are on track, something

does happen between visits. Just as novelists talk about their

characters taking on a life of their own, there's a sense in which a

painting does, too. Whether or not I've consciously mulled things

over, time has passed and I've moved along to a new space. When I

revisit the work-in-progress, new possibilities present themselves,

solutions to problems seem possible, next steps are clarified. It's a

stretch to call this a "dialogue" with the painting, but it's a good

feeling when we're cookin' along together.

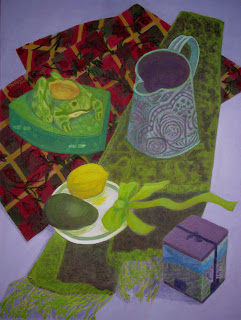

Earlier this year, I decided to capture the view toward my studio

window, an idea that's intrigued me every winter, when houseplants and

wintering-over geraniums are clustered together, leaning into the

scarce light. "Winter Window," it would be called, and this year I'd

do it instead of just thinking about it. The scene before me, as shown

in the photo, was my guide. As I began, I imagined myself down at geranium-level, looking up

through the leaves. I had the plants and the window as models, but

the viewpoint was entirely imaginary. For the first week or so, it

was quite stimulating, but gradually I began to realize that I had no

impulse to check on it during the day. I knew nothing was happening

behind closed doors; somehow, it wasn't giving back.

When JT asked how I was doing and I heard myself say, "Oh, I'm

grinding along on this dumb painting," I knew it was pointless to

spend more time on it. The top part was too empty, and the bottom

part too full -- and no tentative salvage operations made a

difference.

I recalled the words of one of my mentors: Sometimes you can learn

more from a work that fails than from one that succeeds. I recalled

another painting on which I'd pulled the plug -- and the lesson I'd

learned then (two years ago) but forgotten. Some artists could bring

off my idea of "being down among the geraniums" -- but for me, working

only from an idea -- from "imagination" -- is risky business. I need

to start with a strong structural underpinning, a solid pictorial base

-- a lesson I'll try to remember.

So: Goodbye, Winter Window. Maybe another time, in a different way.

For now, it's been turned upside-down and received some preliminary

marks for an entirely different painting that will go over it.

You can view its short failed life -- and ponder how it might be reincarnated here.